Contents:

- Use Rights You Already Have

- Get Permission From the Current Rights Holder

- Unusual Cases

- Publisher Dead Ends

This next part of our toolkit for making your collected scholarly work available online (Part 3) may be the most challenging one — not from a technical perspective, but in terms of requiring patience and persistence. If you’re working through the toolkit in order, you’ve now used Part 1 to make a list of publications you want to upload, and Part 2 to collect and organize copies of each of the publications on that list. Before you move to Part 4 and start uploading your files, you should consider whether doing so might infringe the copyrights of publishers who published your work.

As discussed in Part 2, Collecting your files, when you first write something, you own the copyright in your work and have the legal right to share it however you like, without even checking with your co-authors first. When you publish your work, a publisher typically requires that you transfer rights to them. Whether you have the right to share your work after you sign a publishing agreement, and under what circumstances, depends on the terms of what you signed.

In book publishing, presses have traditionally required authors to transfer copyright ownership to the press, and authors cannot share their books online. However, if your book is older — particularly if it is out of print — you may have options. Please see the section “If you’ve already assigned your copyright, can you get it back?” in this site’s guide to Managing Copyright & Negotiating Publishing Agreements to learn more.

In journal publishing, authors tend to have more rights. Journal publishers also usually require transfer of copyright, or an exclusive license (meaning no one else can use the same rights). Alongside this transfer, however, journal publishing agreements often grant authors certain rights to reuse their own work, including the right to share the author’s accepted manuscript version of their article in an institutional repository. (NOTE: for works written in 2014 or later, UC authors have the right to share their AAM in eScholarship regardless of the specifics of the publication agreement. See more below about UC’s open access policies.)

The publishing agreements for conference proceedings, book chapters, and other short work can vary. They are typically closer to journal publishing agreements than book publishing agreements, especially to the extent that the author is not being paid and the publisher is investing fewer resources in the editing process.

If the set of publications you want to share includes a substantial number of journal articles and similar works, consider relying on the rights you already have through your publication contracts, your publishers’ policies, or UC’s OA policies to share the author’s accepted manuscript version (AAM) of your articles. (Read more about how to locate and identify this version in Part 2, Collecting your files. Keep reading the next section, “Use rights you already have,” to learn more about sharing your AAM versions.

If you can’t use the AAM or prefer not to, and instead plan to use the version of record (VOR), you will generally need to get permission from the publisher of the work, as described further below in “Get permission from the current rights holder.” Two exceptions to this rule are covered towards the end of this page, under “Unusual cases:” if the work was published with a Creative Commons license, or if you never signed a publication agreement.

Use Rights You Already Have

For journal articles and some other short works, authors often retain the right to share the AAM version in their publication contracts. In addition, regardless of the specifics of the publication agreement, you can use the rights available through the UC open access policies to share your AAM if the work you want to share is recent (written in 2014 or later for senate faculty, 2016 or later for other UC employees). You can learn more about UC’s open access policies in the UC OA Policies FAQ.

Check your agreement for language like this example: “an author may share the Accepted Manuscript via non-commercial hosting platforms (such as the author’s institutional repository).” If you don’t have copies of your publication agreements, you can try asking your publisher for copies. For journals, you can also:

- Check the journal or publisher website for sections like “Author Archiving” or “Sharing Options.” These terms may be more generous than the rights you retained in your original publication agreement, but most publishers seem to intend for them to apply retrospectively.

- Look the journal up in SHERPA/RoMEO, a database of article sharing policies of thousands of journals.

Some publishers allow sharing the Version of Record (VOR), the version downloaded from the publisher’s website or a library database, although this is rare. If your publisher is one of them, this will be specified in your publication agreement or on the journal or publisher website.

Because policies will be the same for all articles in a journal, and often for all journals from a given publisher, this is another good time to work in batches. If you’re using a spreadsheet to track your project like we recommend, you can sort your spreadsheet by journal or publisher (see Part 1, Creating your list). You can add a column for “Publisher Policy” and add data like “can deposit AAM in institutional repository after 12 months” or “no rights to post any version.”

Get Permission From the Current Rights Holder

Traditional publishing business models rely on sales and subscriptions. If a publisher is making money by selling access to your work, they might not be happy about you posting a copy that people can read for free. Not all publications are in high demand, however, and you may be able to make the case that sharing your publication will not affect a publisher’s income, especially if your work is older.

First, figure out who controls the rights to distribute your work. Sometimes this is easy, but not always. Journals may switch publishers, and publishers may merge or be acquired by other publishers. Here are some resources to help make sure you ask the right person when you write for permission:

- Your spreadsheet. If you’ve used Google Scholar to create a spreadsheet as described in Part 1, publisher information may already be filled in for many of your publications. It’s a good idea to verify this information with a second source, to make sure the publication hasn’t changed hands since your work was published.

- Search engines and Wikipedia. A regular web search will often turn up the journal’s homepage at its publisher’s website if the journal is still active. If there is a Wikipedia entry about the journal, it will often list the current publisher.

- Specialized databases. For most journals, a quick web search should do the trick. For publications that are no longer active, have changed names, or are otherwise unusual, you may need to work a little harder. Ulrich’s Periodicals Directory is available to all members of the UC community, through your campus library. Search for your title, click on it to see the full record, and then scroll down to find “Publisher and Ordering Details.” If you need help learning how to use Ulrich’s, contact your campus library.

- If none of these are helpful, see our note below on “Publisher dead ends.”

Using this information, figure out which requests you can combine. You don’t want to send any more requests than you have to. If you’ve published works in the same publication, or if you’ve published in multiple journals owned by the same publisher, try to consolidate. This is one of the times when having a spreadsheet you can sort by publisher is extremely useful.

When you have compiled a batch of works whose copyright is owned by the same publisher (or, as may be the case, when you know you have just a single work whose copyright is owned by a particular publisher), assemble your request. Your request should convey two main points: first, you are the author of these works with a strong moral motivation to make sure they’re available; and second, your sharing them online will not harm the publisher’s market. We have provided a template letter with example language you can use.

Download:

- Sample language requesting permission for multiple works

- Sample language requesting permission for a single work

Find an appropriate contact and send your request. Requests like this are not part of a publisher’s regular day to day operations, and it may not be apparent who you should email. Look for an email address for “permissions” or someone with that job title. It is increasingly common for publishers to outsource all permission requests to the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) instead of handling permission requests themselves. The CCC is a company that exists to license works for uses like reprinting, for a fee. You are not a member of the general public looking to use a work you find interesting; you are the author of the work trying to regain some of the rights you originally had. The CCC will quote you a price, and they likely will not allow posting on the open web. They are not who you need to talk to.

You may also find your work hosted in a database or aggregator platform the library subscribes to, from companies like JSTOR or EBSCO. These companies license works from publishers, but they very rarely own the copyrights themselves. Look for a copyright notice or named publisher on the article itself or in the information framing the document, and contact that publisher.

If the publisher you need to contact does not have its own contact for permission requests, try contacting the current editor-in-chief for one of the journals you’re asking about, or a general customer service address. Tell them what you’re working on, say that you don’t think the CCC is the right way for your request to be handled, and ask them to put you in touch with someone who can answer your question. You may wish to include a copy of the request you’ve assembled for them to forward.

Be prepared to follow up. As noted above, requests like this are not part of a publisher’s usual operations. Your request may be mis-routed or forgotten about, and you may have to send it again.

Track your results. Add a column to your spreadsheet for “Permission.” Fill it in with brief status updates like “requested” and “granted.” You may also want to include the dates of emails and who you contacted.

Unusual Cases

You have the right to share your work publicly without further permission in certain circumstances:

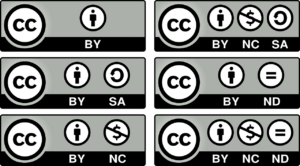

If your work was originally published open access with a Creative Commons (CC) license, you can share it. If you see a CC badge and description, like “CC BY-NC-ND, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives,” you can download a copy and share it on any non-commercial site. Here are what the different CC badges look like:

If you didn’t sign an agreement with your publisher, you can share your work. If you were working with a large commercial publisher or a university press, it was almost certainly standard procedure for them to have you sign a publication agreement. Ink on paper isn’t required; the important thing is whether you agreed to the publisher’s terms. This “signing” has increasingly become digital and is often part of an online submission or editing workflow in journal publishing. But if you were publishing with a smaller independent entity like a scholarly society, it’s possible that they didn’t use a publishing agreement. If you didn’t sign anything, then you haven’t transferred your copyright or given anyone exclusive rights. In other words, you still have the right to share your work. If you’re not sure, you can search your records, or ask the publisher for a copy of what you signed.

Publisher Dead Ends

Sometimes journals cease publication or publishers go out of business, and you can’t tell who, if anyone, has taken them over. If after diligently hunting on search engines and checking Ulrich’s Periodicals Directory (see above) you still have no idea what company or organization you should send your request to, consider whether you might have a “fair use” argument for posting your article online.

Fair use allows reproduction and other uses of copyrighted works – without requiring permission from the copyright owner – under certain conditions. A fair use analysis involves considering four factors, and courts tend to place the most emphasis on two of them:

- The purpose of your use. In your case, your use is for nonprofit educational purposes, which weighs in favor of fair use.

- The impact of your use on the market for the work. If you cannot find anyone to ask permission, then arguably there is no market for the work for you to impact, and this also weighs in favor of fair use.

You can read more about fair use at the UC Copyright site. If you conclude that sharing your work in eScholarship is a fair use, you can deposit it. Under the terms of UC’s Copyright and Fair Use Policy, “In the unlikely event of a copyright infringement claim, the University will defend its employees who acted within the scope of their University employment and who made use of the copyrighted work at issue in an informed, reasonable, and good faith manner.” A copyright infringement claim in these circumstances seems especially unlikely: if you could not locate a copyright holder from whom to request permission, there is probably no one to object to your use.

Before giving up on identifying a publisher, you can also search the Copyright Clearance Center’s (CCC) Marketplace to see if anyone is claiming the right to license the work. As explained above, this is not the appropriate place to seek permission for your kind of project, but if the publication you’re interested in hasn’t been claimed in the CCC Marketplace, that’s further evidence that there’s no market for that publication. If it has been claimed by a publisher, you can try contacting that publisher. Be aware that some of the CCC’s information is inaccurate or out of date.